Hi! This material will show you how to build your own battleship game with python. This is an intermediate project, if you still haven't done the beginner tutorials, you should try those first (or ask for some extra help with this one, that's fine too!).

When programmers write a bigger program like this one, they don't normally sit down and write the whole thing from top to bottom. The best way to do it is to solve just a part of the problem, run it and see that it works (or fix it if it doesn't) and only then add new parts. So that's the way we'll build this too. Try running the program and see and understand what it does at the end of each section before moving on!

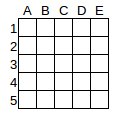

There are many ways and variants of the battleship game, so let me first clarify about the one we're building before writing code. Each player will have a 5 squares by 5 squares board like this one:

Note that columns are letters (A, B, C, D, E) and rows are numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5); some people do it the opposite way, but this one also works.

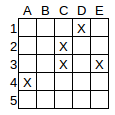

One of the players will choose 5 squares where their battleships will go, any square is fine. for example, let's say our players are called Alice and Bob. Alice chooses 5 squares and marks an X on them to represent their battleships:

She will choose board locations by typing in the column(letter) and row (number) of each battleship. For example, to enter

the battleship on the left, she will enter A and 4, because the ship is in the column labeled A and the row labeled 4.

She will have to do this 5 times, to tell the computer the location of her 5 battleships.

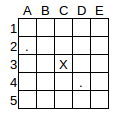

After this Bob can start guessing. Turn by turn he will type board locations (also by letter and number) and the computer will

tell him if it was a hit or a miss. Bob will start with a blank board (because he doesn't know where Alice's ships are), and after each guess he'll mark an X if there was a hit, or a dot (.) if there was a miss. For example if his guesses are D4, C3, A2, his board will look like this:

In a normal game of battleships Bob would also would have his own ships and Alice her guessing board, but to make the program shorter we will just make this simple version. A nice project for taking home is to modify this into the full game.

The program we're writing will need to remember the board of each player. When a program has to remember something that means

that you have to store it in a variable; we'll call it board. But python variables can store numbers like 42 or text like "lazy dog" in them, but they can not store battleship boards, or can they?

The trick the programmers use in this case is finding a way that they can turn something they want to remember (like a battleship board) into something that Python can understand. There are some tricks that we can use this time:

- Each square in the board can be represented by a string:

' 'if the square is empty or'X'if there's a battleship in it. - Each row of 5 squares can be represented by a list of 5 strings like the one above

- The board has 5 rows, so you can represent them as a list of lists like the one above (yes, you can pust a list inside another list!).

Let's do that. Create a new python file (for example battleship.py) and enter the following:

# A board is a list of rows, and each row is a list of cells with either an 'X' (a battleship)

# or a blank ' ' (water)

board = [

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

]That's an empty board!

Now, when the users enter a position like C4, we need to translate it to a specific location on the list. Remember that python lists count their position from zero, not from one. So we need to convert A, B, C, D, E to 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 for columns, and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 to list positions 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 for rows (this may sound a bit confusing at first, don't worry if you don't follow and try the code). So C4 would be the column with list position 2, and the row with list position 3, and we'll write that as board[3][2] . The row translation is easy (just substracting 1 from the original number), but converting letters to numbers is a bit more complicated. We'll use a dictionary, which works like a table to say which number value corresponds like a letter value, we can write it like this (add this to the bottom of your python file)

# We want to refer to columns by letter, but Python accesses lists by number. So we define

# a dictionary to translate letters to the corresponding number. Note that Python lists start in

# zero, not in one!

letters_to_numbers = {

'A': 0,

'B': 1,

'C': 2,

'D': 3,

'E': 4,

}Note that the example code in this project has comments (the lines that start with a # mark). You don't need to type them down if you like, but they should help

you understand the example code. Also, if you do type them and take the code if you, it will be easier to remember what each

piece of the program does. If you thing something is interesting or that you learned something new, you can also add your own comments to remind you of that!

Now let's make it possible to add 5 battleships to the empty board. Add this code to the bottom of your program:

# We want 5 battleships, so we use a for loop to ask for a ship 5 times!

for n in range(5):

print("Where do you want ship ", n + 1, "?")

column = input("column (A to E):")

row = input("row (1 to 5):")

# columns are letters, so here we use the dictionary to get the number corresponding to the

# letter

column_number = letters_to_numbers[column]

# The player enters numbers from 1 to 5, but we have to substract 1 to use python lists that

# start on zero.

row_number = int(row) - 1

board[row_number][column_number] = 'X'

# Show the board, one row at a time

for row in board:

print(row)At this point you should be able to run this program and use it! You will see that it allows you to place ships and shows you the board after each ship is placed. The board looks a bit ugly with all those brackets and commas (which are shown in python lists), but don't worry about it; as I said when we started, it's important to get simple things running and working, and you can slowly fix and improve everything.

If you try our program for a bit, you'll notice that it may be a bit annoying with you when you make a mistake. if you mistype X instead of C (they are right next to each other on the keyboard!) you'll see an ugly error message and the program will crash. Also, if you add a ship to a position that already has a ship, the program will happily mark an X where

already was one (which does nothing) and move forward, so you will end up with one less ship.

We can actually use if statements to check for these situations and show a warning to the user.

To prevent adding ships twice in the same place, you can check that there's no X in the board right before placing a new one. The line that places a new X is the one that reads board[row_number][column_number] = 'X'. You can add the following code right before it:

# Check that there are no repeats

if board[row_number][column_number] == 'X':

print("That spot already has a battleship in it!")Now that you're modifying code you'll have to be extra careful with the indentation. Remember that Python loops and ifs work differently depending on the code is inside (a bit to the right) or outside (at the same level), and getting this right may require understanding a bit the code and being careful. Ask for help if you get stuck or get results that look wrong

To check that the user enters a valid letter, you can add this right after the column is asked from the user (after the line that starts with column = input ...:

if column not in "ABCDE":

print("That column is wrong! It should be A, B, C, D or E")To check that the user enters a valid number, you can add this right after the column is asked from the user (after the line that starts with row = input ...:

if row not in "12345":

print("That row is wrong! it should be 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5")Note that this code we added does not prevent the user from making a mistake, and if she does she will only get an error message but the program will crash or overlap ships anyway. It's an improvement but we'll improve some of this later (and the rest can be done after the dojo if you like!)

Run the program and try it! See what happens when you type something wrong, or when you add a battleship twice at the same place!

Now that Alice has enterede the ships, she can leave the keyboard and give it to Bob so Bob can guess. To make this interesting Bob shouldn't have been looking at Alice's screen while he was placing the battleships. However, if he sits at the computer right away she will see the board that was printed for Alice and was placed on the screen, so we should hide them. A simple way to do it is to just print a lot of blank lines. Add this to the bottom of your code:

# Now clear the screen, and the other player starts guessing

print("\n"*50)Now you can add the guessing code. It is quite similar to the previous part of the program except that:

- We don't know exactly how many guesses it will take bob to find all the battleships. So we use a

whileloop instead of aforloop. We count the number of correctguessesin a variable, and the loop should continue if some of Alice's ships haven't been found yet (that is,guesses < 5) - At the bottom of the loop there is an

ifthat checkes Alice's board for anX, and shows a hit or miss message. That part of the program is also in charge of updating theguessescounter:

# Keep playing until we have 5 right guesses

guesses = 0

while guesses < 5:

print("Guess a battleship location")

column = input("column (A to E):")

if column not in "ABCDE":

print("That column is wrong! It should be A, B, C, D or E")

row = input("row (1 to 5):")

if row not in "12345":

print("That row is wrong! it should be 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5")

# columns are letters, so here we use the dictionary to get the number corresponding to the

# letter

column_number = letters_to_numbers[column]

# The player enters numbers from 1 to 5, but we have to substract 1 to use python lists that

# start on zero.

row_number = int(row) - 1

# Check if there was a hit or a miss

if board[row_number][column_number] == 'X':

print("HIT!")

guesses = guesses + 1

else:

print("MISS!")

print("GAME OVER!")After this you should be able to play this game with a friend. Run it, place the battleships, after the 5th the screen will be cleared and you can leave the comptuer to your friend and see how long he takes to guess!

Congratulations! You have already built a working game. If you still have time left or want to work more on this at home, the rest of the guide gives you some ideas on how you can improve this and learn some additional Python tricks.

As I said before both loops in the game (placing the battleships and then guessing their locations) have a lot of similar code. That's actually a sign that the code may be improved. Repeated code can be placed inside a function that can then be used in all the places where there is a repetition. Doing this makes the program shorter and easier to understand. Also, if later we find a bug or improve the code of the function, the new code is used in all the places where the function is called instead of having to fix it in many places.

Let's take the repeated code and put it into a function, at the top of the file:

# By writing this as a function, we don't have to repeat it later. It's less code, it makes

# the rest easier to read, and if we improve this, we have to do it only once!

def ask_user_for_board_position():

column = input("column (A to E):")

if column not in "ABCDE":

print("That column is wrong! It should be A, B, C, D or E")

row = input("row (1 to 5):")

if row not in "12345":

print("That row is wrong! it should be 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5")

# The code calling this function will receive the values listed in the return statement below

# and it can assign it to variables

return int(row) - 1, letters_to_numbers[column]Some things to notice here are:

- The

defline defines the function and allows you to give it a name. It's important to choose a name that makes it clear what the function does, to make more clear the code that calls the function later. - The function ends with a

returnline telling with values will be the ones that are useful at the end of he function. when we ask for a board position, what we need at the end is the list positions for the row and column, so that's what the function calculates - When you write the function Python does not run the code in it just remembers for the future under the name you give it. The code will actually be run when you have a "function call", which is the name with the function with brackets to the right:

ask_user_for_board_position(); this actually can be used in an assignment to get the returned value (or values)

After defining the function you can remove the repeated code and add a new line near the beggining of the battleship positioning code, which should look like:

# We want 5 battleships, so we use a for loop to ask for a ship 5 times!

for n in range(5):

print("Where do you want ship ", n + 1, "?")

row_number, column_number = ask_user_for_board_position()

# Check that there are no repeats

if board[row_number][column_number] == 'X':

print("That spot already has a battleship in it!")Note that you should just add the row_number, column_number = ask_user_for_board_position() (the rest should be already there). This is the function call, and after this line the row_number and column_number variables will have whatever the function returned, which should be the row and column numbers corresponding to the location on the board the player chose.

Now, you can change the guessing code to look like this:

while guesses < 5:

print("Guess a battleship location")

row_number, column_number = ask_user_for_board_position()

# Check if there was a hit or a missAgain, only a new line was added here, in place of all the code that we removed and placed inside the function.

If you run the program now, it should work exactly like the one before, but it's now simpler and shorter. This is something that programmers do a lot and has a name: "refactoring". When refactoring, you take a program and change so it does the same, but in a better, simpler way. This makes it easier to add futures later on.

Now that the location asking code is a function, we can add improvements and fixes to it, and it will benefit all the parts of the code that use it.

For example, have you noticed that if the user enters an invalid row or column (like "Z 200") the program crashes? It would be nice to fix this, sometimes people shift their fingers a bit and press the wrong key. We'll make sure that the row and column are valid values, by asking for them again if the player made a mistake. Note that we use a while loop, so if the player makes several mistakes in a row he will be asked repeatedly until entering a correct value:

Rewrite the function as:

# By writing this as a function, we don't have to repeat it later. It's less code, it makes

# the rest easier to read, and if we improve this, we have to do it only once!

def ask_user_for_board_position():

column = input("column (A to E):")

while column not in "ABCDE":

print("That column is wrong! It should be A, B, C, D or E")

column = input("column (A to E):")

row = input("row (1 to 5):")

while row not in "12345":

print("That row is wrong! it should be 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5")

row = input("row (1 to 5):")

# The code calling this function will receive the values listed in the return statement below

# and it can assign it to variables

return int(row) - 1, letters_to_numbers[column]Now you can see that both the ship placement and the ship guessing parts of the program are improved at the same time! That's the power of functions!

There's more code that could be moved to a function: The code that displays a board is used when positioning the inital ships. That will allow us to later reuse that (without copy and paste!) to show the board while guessing.

We can add this function at the beginning:

def print_board(a_board):

# Show the board, one row at a time

for row in a_board:

print(row)Note that this function has something new: it says a_board between the brackets, and uses that as a variable inside the function. This a_board variable exists only within the function, this kind of variables are called argument. When the function is called, you need to pass a value (which board we want to print) within the brackets of the call, and that value will be assigned to a_board.

Somewhere in our code we want to print the board in the variable called board. That will be done by calling print_board(board). As an excercise, find which code to remove and replace it with print_board(board).

The game can be played as it is but it's hard to remember which places we've shot and which ones were hits or misses. It would be easier to play if we could see a board with our previous guesses and its results. To do that we need to remember more information, so let's use a variable!

guesses_board = [

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

[' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' '],

]This works like our board variable, but instead of having the whole map of battleships, we just want to store a space for locations that we don't know about, an 'X' for a hit, and a dot '.' for a miss.

To store that information, we can update guesses_board right after printing a hit:

guesses_board[row_number][column_number] = 'X'And the same right after printing a miss:

guesses_board[row_number][column_number] = '.'At the end of the guessing loop we can use our brand new function to print the guesses board, now that now we have to boards, but thanks to the function argument (the a_board within brackets) we can choose which board to print when calling the function:

print_board(guesses_board)If you try this now, the game should me much easier to play

When boards are printed, they are readable but a bit ugly, with a lot of symbols that python adds like square brackets, and commas, and quotation marks. We can improve a bit our print_board function to make it look better. Try replacing the function with this:

def print_board(board):

# Show the board, one row at a time

print(" A B C D E")

print(" +-+-+-+-+-+")

row_number = 1

for row in board:

print("%d|%s|" % (row_number, "|".join(row)))

print(" +-+-+-+-+-+")

row_number = row_number + 1Now you should see the grid lines, and the row and column labels. Much better, isn't it?

There is a small bug in the code that we have written. Sometimes small things slip by us, or even we do it on purpose because it's easier to get something simple working and improve the details later. That's perfectly fine and fixing bugs that you didn't noticed or that you left for later is a normal an important part of programming.

Our bug is that if a player enters the same location many times, the program allows that; even more, it allows to cheat a bit: if I'm playing and I find a battleship at B 3, I can the keep shooting at B 3 and the program will happily see that I keep hitting and counting correct guesses up to five. That's becauses the program does exactly what we tell it to, and we never told it that the guesses have to be in different places of the board. Let's fix that:

Add the following code after asking for a guess:

# Check that there are no repeats

if guesses_board[row_number][column_number] != ' ':

print("You have already guessed that place!")

continueWe are using now our guesses_board also to see if the player has already used the location, it should only have spaces (' ') for new locations, and if it has something else, it means is a repeat. The continue statement tells Python to go back to the beginning of the loop, so all the remaining code of checking if it is a hit or miss will be skipped.

This is the end of this tutorial. Of course, at this point you might have some ideas of what you would like to change or improve in the game, so feel free to try different things. Hope you had fun!